Die Zukunft von Kunst und Kirche

|

Aesthetics vs. Erotics?The Nude in Hermann Cohen’s Aesthetics[1]Ezio Gamba AbstractA central topic in Cohen’s Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls is the artistic representation of the human figure; in Cohen’s reflections on this topic, the nude has a fundamental importance. The first aim of this paper is to examine Cohen’s theses on the role of the nude in figurative arts, as well as his comments about sculptural and pictorial works representing nude figures. This will bring us to take into consideration Cohen’s judgement about eroticism in art. Some brief considerations about the nude in contemporary art, and above all in photography, will be expressed in order to evaluate the topicality of Cohen’s aesthetics concerning this theme. These considerations, however, will make it necessary to rethink Cohen’s judgement regarding eroticism in art. I. The Figure and the NudeA central topic in Cohen’s Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls[2] is figure, because pure feeling--which is the fundament of every artistic creation--is (in its psychological interpretation) love for the human being. This love is productive: it is not love for an already given human being, it is production of the human being itself. This statement has a double meaning: first, pure feeling is production of the aesthetic self; in addition, it is also production of the human being as an object (the main object) of artistic representation or description. This production of the human being as the main object of artistic representation or description takes place in different ways in the different arts; the description of a fictional character or the narration of his story in a novel is certainly different from the representation of a man or a woman in painting or in sculpture. In painting or in sculpture, the human being is represented as figure, in its duplicity of male and female. Cohen, however, does not examine the concept of figure only in the second volume of the book, which is the volume where he specifically examines the different arts. On the contrary, the concept of figure is more deeply examined in the first volume (which is devoted to the elaboration and exposition of Cohen’s general aesthetic theory), with reference to the way the human being is the main object of artistic representation as produced by pure feeling. The way this production takes place in painting or in sculpture is certainly not the only one, and Cohen does not attribute to it a more fundamental role in comparison to the description of literary characters in novels or poetry; however, the pictorial or sculptural figure is the kind of representation of the human being in which the central role of the human being as the main object of artistic representation or description is maximally evident; this is even clearer in sculpture than in painting, because in painting the figure is usually inserted in a background, whereas in sculpture it is mostly represented alone. This particular evidence of the production of the figure in sculpture in comparison to the different ways the human being can be the object of other arts is confirmed, according to Cohen, by the decisive role that sculpture has had for the origins of philosophical aesthetics, and above all for Winckelmann’s thought, which was a fundamental step in the history of the birth of aesthetics[3]. Cohen devotes many reflections to the topic of the figure, and it would be impossible to summarize them here.[4] What is important here is that the human being represented as figure has to be the object of love, and this love produces the human being--it does not merely address the human being as an object that is already given. Love produces the human being in its original being, in comparison to which the historical or social features of the human being become inessential and can also be excluded from the representation; as a consequence, the figure represented by painting or by sculpture is par excellence the nude figure. The nude is the representation par excellence of the individual produced by love and endowed with universal and ideal value. Which nude figures are really important for these reflections? It should appear clearly as a consequence of what has been stated before (i.e., the particular meaning the nude has for aesthetics consists in the fact that in nude figures we see that pure feeling produces the human figure so that its social or historical features become so inessential that they can be excluded from the representation) that not every nude figure is equally important for our reflections; the most important nude figures are those which have no reference, or almost no reference, to a precise historical moment or to an identifiable narration. If we consider, for example, one of the many paintings representing the biblical episode of Susanna and the Elders, we shall find in the painting the figure of a nude woman;[5] however, Cohen’s reflections about the nude do not mainly concern this kind of image, not only because the nude figure of Susanna is just one of the elements of the painting, but also because the painting represents a specific story.[6] Cohen’s reflections refer on the contrary mainly to figures that are as lacking as possible of historical or social features and of references to history or to a specific story. Therefore, perfect examples of those nude figures are ancient Greek ephebes, or other figures (both male and female) of the same kind:[7] figures that, in their nudity, do not contain any reference to a story, an identity, a social role. We can say that the main characteristic of these figures is not merely that we do not know who they are, but also that there is no authentic meaning in wondering about their identity, because each of them is an individual that (even if it is authentically individual in its representation)[8] has as its sole feature the dignity of the human being as produced by love.

In the second volume of Asthetik des reinen Gefühls, in the chapter about sculpture, Cohen reflects on many figures of gods and athletes of Greek sculpture, and many of them are obviously nude figures. However, in the first volume, when he deals specifically with the topic of the nude as the main example of the production of the human figure by pure feeling, he takes into consideration two nude figures, with reference to some statues by Praxiteles or ascribed to him. The first figure is Eros: he is a nude figure that represents love itself; the importance of this figure for aesthetics is clear: pure feeling, as love for the human being, produces a figure which is love itself. Moreover, Eros has a female equivalent, Aphrodite, and often we see Eros represented as a secondary, attributive figure in the artistic representation of this goddess. Like Eros, Aphrodite represents love, but she represents it as a female figure; taking into consideration Praxiteles’ Cnidian Aphrodite, Cohen highlights that in this statue nudity is not a full deprivation of every element added to the figure. Here we see Aphrodite’s clothing, but Aphrodite holds it in her hand, as she is putting it down. She is not merely nude, she has just finished disrobing, so that her figure is visible in the essentiality of the nude human being produced by pure love.[10]

The most significant feature of the Satyr, with respect to the topic of the nude, is that he represents the sex drive (Geschlechtstrieb).[16] Since the Satyr is object of love, however, the sex drive represented by him does not remain mere animal drive, but it reveals itself as love;[17] the Satyr, Cohen states, becomes Eros[18] (and so, the figure that lies on the inferior boundary of humanity, i.e. the boundary between the animal and the human, is brought to the superior boundary of the human, and becomes a divine figure). Eros is not void of reference to sex, he is first of all the representation of sexual love; however, Cohen reminds us that, in Greek culture, sexual love is only the first meaning of Eros; as Plato teaches in his Symposium, sexual love is just the first step to nobler kinds of love, which culminate in love for beauty itself, for beauty as idea.[19] In the figure of the Satyr the sex drive does not remain a mere animal drive, but rather it reveals itself as love thanks to Humor, and in the figure of Eros sexual love is just the first step towards love for beauty itself--in figures like ephebes, which are the product of pure love for the human being in its beauty and in its dignity without any hint to a precise identity, every reference to sex is completely overcome, every bit of sexual attraction is completely transfigured into chaste admiration for the beauty of the human being. Cohen is indeed clearly concerned to explain as clearly as possible that in these representations of nude figures there is no eroticism in the most usual meaning of the term, and that the love which produces these figures is radically different from erotic desire. As erotic desire is excluded, also the moralistic negative judgment about nudity is rejected by Cohen with reference to these figures. A clear sign of the aesthetic authenticity of the representation of the nude is the overcoming of these two attitudes, which are opposed, but which are also both far from the purity of feeling. In the authentic artistic representation, the human being represented in its nudity is the object of a love that is not desire, and the ostension of the body is not brazenness or exhibitionism (as could be judged by a dogmatic religious morality which, for the fear of sin, does not tolerate that the human body remains uncovered), but authentic expression of beauty. Modesty itself, according to Cohen, is not excluded from representations of this kind, but it is brought back to its authenticity, so that it is not shame, fear of sin or sense of guilt, but wonderment for the beauty of the human body.[20] The meaning of these reflections by Cohen is not merely that we can empirically observe that these representations do not rouse erotic desire, or do not seem to be realized in order to cause erotic attraction; by these reflections he rather shows that pure feeling, or pure love, must not be confused with erotic desire. Eroticism in art appears to be considered by Cohen as a hindrance to the purity of feeling. What can be the reason for this judgement about eroticism in art? Perhaps we could think that this judgment is due to a confusion of a moral (or moral and religious) concept of purity and impurity with the aesthetic concept of purity of feeling; however, this understanding of Cohen’s theses would seem to forget that his rejection of eroticism in relation to the representation of nude figures is, at the same time, a rejection of the moral and religious aversion to nudity for fear of sin; it is necessary to search for aesthetical – not moral or religious – grounds for Cohen’s consideration of eroticism in art as a hindrance to the purity of feeling. The aesthetic reason for Cohen’s judgement about eroticism in art simply lies in his radical distinction between sex drive or erotic desire and pure feeling; erotic desire is not pure feeling, so it cannot be the feeling art is founded on. Sex drive is rather an affect,[21] that is, a feeling that is not pure, in the sense that it does not produce its object, but is rather related to a given object; this relation to an object that is already given and that is not produced by feeling itself is the hindrance eroticism gives to the purity of feeling. In the chapter of the second volume of Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls devoted to lyric poetry, Cohen’s rejection of eroticism in art is even more explicit than in his reflections about nude figures, and brings him to express a negative judgement towards the Venezianische Epigramme of his beloved Goethe.[22] According to Cohen, lyric poetry is essentially love poetry, poetry about love between man and woman; consequently, lyric poetry cannot forget the bodily dimension of the lovers and of their love. However, poetry has to be founded on pure feeling, on pure love, not on erotic desire (which is an affect); so, the carnal dimension of the lovers and of their love has to be completely transfigured, idealized.[23] As in the nude figures of the ephebes, in lyric poetry eroticism has to be transfigured into chaste love for the human being. II. Nude Figures in PaintingCohen’s reflections about the artistic representation of nude figures are developed with reference to sculpture, more than to painting; this is consistent with Cohen’s consideration of the nude figure as the representation of the human being in its original being, in comparison to which every social or historical feature becomes irrelevant and is cancelled or reduced to the minimum; sculpture is indeed par excellence the art that brings to representation the nature of the human being (Natur des Menschen)--i.e. its unity of body and soul--in a single figure, whereas in painting the other aspect of the figure--which is named by Cohen ‘the human being of nature (Mensch der Natur)’--is predominant.[24] This means that, in painting, the human being is mainly represented as linked to its environment (not only his natural environment, but also his social and historical one). Therefore, sculpture is the art form to which the nude figure mainly belongs.

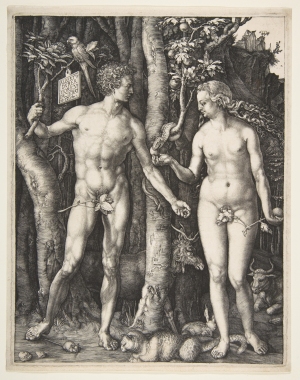

Some of these reflections simply restate Cohen’s already examined views; the clearest example is Cohen’s comment about Dürer’s engraving known as Original Sin or Adam and Eve (not to be confused with the engravings representing Adam and Eve in Dürer’s cycle of the Small Passion): Cohen’s judgement is that these nude figures are ‘sublime beyond the ambiguities of sensuality’.[25] A similar judgment is given by Cohen regarding the nude figures represented in some of Rembrandt’s works, which Cohen mentions without examining any of them in particular.[26] In these works, the represented nude figures (Cohen mentions only female figures: Danae, Antiope, Susanna and Diana) are always young and beautiful, and there is no lust or sensuality in them (with the exception of Eve at the moment of sin). However, we have to notice here a stupefying incongruity in Cohen’s comments about nude figures in Rembrandt’s works; this judgment about Rembrandt’s representations of nude women, expressed by Cohen in the chapter of the second volume of Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls about painting, can be a little surprising, because Cohen considers Rembrandt as one of the main artists of Humor for his representations of ugly (or, at least, far from the classical or traditional type of beauty) human beings as objects of love. Should we think that this is not the case of his representations of nude figures? Actually, in the first volume of Cohen’s book, in the pages devoted to Humor in the chapter about the idea of beauty, we find some statements that clearly contradict Cohen’s comments mentioned above. Here, after noticing that the representation of nude figures is infrequent in Rembrandt’s works, Cohen states that in the representation of nude figures as well, Rembrandt’s interest is always mainly devoted to the problem of ugliness, as it is possible to see in his Susanna[27] (which, in the second volume of the book, is on the contrary listed among Rembrandt’s works that should show us that in his works nude figures are always young and beautiful). In both contexts, Cohen comments on Rembrandt’s works in contrast to Rubens’. In the context of the first volume, Cohen draws attention to the importance of the role of Humor in Flemish painting; Rubens, according to Cohen, does not belong to the tendency of Flemish painting that is characterized by the centrality of Humor, because he mainly pursues the absolute beauty of the figures he represents, and often reaches it. However, there are also many paintings by Rubens that exhibit sensuality in its crudity. Rubens’ work that is mentioned by Cohen as the clearest example of this is a painting representing a bacchic scene, which is in the Uffizi Gallery Museum in Florence (the main figure in this painting is generally identified as a nude fat Bacchus, but Cohen believes, on the contrary, that it represents an old fat maenad). Here, as in the figure of the Satyr, we see nude figures that are at the boundary between humanity and animality, and their ugliness is an expression of their sensuality. However, contrary to Praxiteles’ Satyr, these figures, according to Cohen, are not objects of Humor; the reason, paradoxically, is that the power of Rubens’ phantasy in creating these figures and the admiration this power rouses in us prevent us from feeling sadness for their ugliness, for their distance from the ideal, for their belonging to the inferior boundary of humanity. Without this sadness, without the recognition that this sensuality is far from the aesthetic ideal of the human being, Humor is impossible. So, we can admire these figures (or, perhaps better, we can admire Rubens’ phantasy that created them), but we cannot love them; we have however to remember that art in general, without love for human nature, is a failure. Here Cohen counterposes Rembrandt’s works against Rubens’, showing that Rembrandt is a great painter of Humor, and that in his works he represents figures that are ugly (or far from classical beauty) as objects of love. Whereas the works of Rubens that Cohen refers to in this context represent mainly nude figures, Cohen states that nude figures in Rembrandt’s works are rare; the contrast between Rubens and Rembrandt, here, is not an opposition between two ways of representing nude figures, but between two ways of representing ugly figures; the nude, in these considerations by Cohen about Rembrandt’s work, has a secondary role. On the contrary, in the context of the second volume, the contrast between Rubens and Rembrandt directly concerns the representation of nude figures. Here Cohen mentions Rubens’ cycle of Maria de’ Medici as an example of how nudity is used by painters as a way to make ugly human figures presentable, by providing their representation with stirrings of sensuality. In representations of nude figures like the ones in this cycle, therefore, we find a connection of sensuality and ugliness. Here Cohen counterposes Rembrandt against Rubens because Rembrandt, in the same line of Tiziano, employs nudity for the representation of beauty, not of ugliness; nude figures in his painting are always young and beautiful.

Cohen counterposes Rembrandt’s representations of nude figures not only to Rubens’, but more generally to a whole genre of pictorial representations, namely the representation of nude figures of old (and ugly) women; this is a pictorial theme in relation to which, according to Cohen, even many great artists like Dürer and Rubens have shown themselves as inadequate. Perhaps we could expect to find here a fertile field for Humor; it is indeed clear that nudity gives evidence for the beauty of a beautiful body, but also to the ugliness of an ugly body. However, art can produce the figures of ugly human beings as loveworthy, as objects of love; this is what Cohen calls Humor, and it is for him one of the main features of art, if not the most important one. Despite this possible expectation, Cohen does not examine any pictorial works representing old nude women with Humor as objects of love. Besides Rubens’ above mentioned works, Cohen’s main reference for this topic are two engravings by Dürer, which are very different from his already examined engraving representing Adam and Eve in their youth and beauty: The Four Witches and The Great Fortune. Here as well, sensuality and ugliness are narrowly connected; Cohen states that sensuality is generally excluded from Dürer’s works, and that we can find it only in some of his engravings, where it appears under the mask of ugliness accompanied by the stirring of nudity. Cohen asks the question if this sensuality or this ugliness can be loveworthy,[28] but gives a negative answer: here sensuality or ugliness is exposed to derision, so the nudity of those figures has neither the innocence of Eden, nor authentic pictorial beauty.[29] Against the failures of several great artists in the representation of nude old women, Cohen does not counterpose a better way to represent those figures (to represent them with love, with Humor, as we can expect), but rather the work of artists that do not represent them at all; he indeed praises Rembrandt because he (as Tiziano) has not taken this dangerous path, but on the contrary he has always employed nudity for the representation of beautiful figures.[30] The representation of old nude women, hence, seems to be a failure not for the particular features of the artworks that are mentioned as its examples, but in itself (Cohen indeed points not only to the fact that the substitution of flaccid masses of flesh to the clear lines of a young body is a transgression of the principle of form,[31] but also at the eccentricity of the eroticism that finds its stirrings in old and ugly bodies). Cohen recognizes in the constant association of nudity and beauty by Rembrandt and Tiziano (even if the second is only briefly mentioned) an opposition to ‘any scepsis’,[32] but he does not explain this opposition; probably we have to understand the mentioned scepsis as the aesthetic scepticism about the possibility that art could achieve authentic beauty, representing beautiful and loveworthy human beings in their splendour, or about the possibility that human beings could appear to be perfectly beautiful in art. Tiziano’s and Rembrandt’s nudes seem to be a refutation of this scepticism; however, we should remember that, following Cohen’s general aesthetic theory, the very identification of aesthetic scepticism with this kind of distrust is, in turn, aesthetic scepticism; an authentic confidence in art should include not only the recognition of the possibility of art achieving authentic beauty and representing beautiful and loveworthy human beings in their splendour, but also the recognition of Humor, of the possibility of art representing ugly human beings as loveworthy. With reference to the representation of nude figures, Cohen seems to fall into the aesthetic scepticism he fights by the notion of Humor, which is so central in his aesthetics; in the nudity of old women, Cohen finds only Bloßstellung,[33] a German word that etymologically could mean uncovering or denudation, but that actually means exposing someone’s flaws or faults. This exclusion of the figures of nude old women from the objects of Humor as the possibility of representing ugly human beings as loveworthy seems to be an inconsistency in Cohen’s aesthetics. This inconsistency is connected to the contradiction between Cohen’s different statements about nudity in Rembrandt’s works: Cohen can highlight Rembrandt’s Humor (as the representation of figures that are far from classical beauty as being loveworthy) even with reference to the nude, as he does in the first volume, but when, in the second volume, the topic is the representation of old nude women, Cohen does not acknowledge that Rembrandt’s nude female figures, for being far from classical beauty, can have any similarity to this genre of representations. On the contrary, he distances Rembrandt from this theme and states that his nude figures are always young and beautiful. If we consider the figure of Susanna painted by Rembrandt, we could maybe think that Cohen’s comments on this figure are not mutually incompatible and are perhaps both valid: Susanna is certainly young, and we can consider her to be beautiful, even if her beauty is different from the classical type of beauty (Cohen himself states indeed that the ugliness that is a central theme in Rembrandt’s paintings is not the ugliness of sensuality, the ugliness of the Satyr, but consists in the fact that his figures are far from the classical type of beauty).[34] Yet, because of this difference from the classical type of beauty, the representation of this figure as loveworthy can be an example of Humor. However, this consideration cannot eliminate the contradiction between two of Cohen’s statements; the first, that Rembrandt’s main theme even in his rare representations of nude figures is the problem of ugliness; and the second, that Rembrandt, as Tiziano, does not employ nudity for the representation of ugliness, but of beauty. This contradiction is a clear sign of a difficulty in Cohen’s reflections on artistic representations of nude figures that are far from the sublimity of Greek ephebes or of Dürer’s Adam and Eve (a sublimity that put them, as we have seen before, ‘beyond the ambiguities of sensuality’). In light of these considerations, Cohen’s dubious choice of Praxiteles’ statues, as examples par excellence of the representation of the Satyr, can reveal itself more significant and problematic than it could have appeared before: in Cohen’s aesthetics, there are several paradigmatic examples of Humor being the possibility of art representing ugly human figures as loveworthy (like Raffaello’s portrait of pope Leo X in the Uffizi or Rembrandt’s portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels in the Louvre--which are both dressed figures) but the nude figure of the Satyr is the one that brings Humor to his most significant expression--because the Satyr is not merely a ugly human being, but is the figure whose ugliness testifies that he belongs to the inferior boundary of humanity. However, though we can perhaps agree with Cohen’s judgement according to which the figure of Leo X painted by Raffaello is ugly and the face of Hendrickje Stoffels painted by Rembrandt is clearly far from classical beauty, and though we can find Cohen’s reflections about the Satyr as a general artistic subject convincing, it is unlikely that we can consider the figure of the Satyr as represented by Praxiteles ugly. Despite his pointy ears, Praxiteles’ Satyr seems indeed to be a sublime figure like Greek ephebes or Dürer’s Adam and Eve, or at least to be more similar to these sublime figures than to a figure like Leo X. Cohen’s important reflections about the Satyr as a general artistic subject should be exemplified by a ugly nude figure, but the main example given by Cohen is, on the contrary, a sublime nude figure; dressed figures like Leo X or Hendrickje Stoffels are clearly better examples of Humor. It seems here that, in Cohen’s view, the representation of a very ugly body (not simply of a figure that is far from classical beauty, as Rembrandt’s figure of Susanna) in the nude (its Bloßstellung) is not really compatible with the representation of the figure as an object of love. This, however, clearly seems to be inconsistent with Cohen’s theory of Humor, and could be judged to be an interference of Cohen’s personal artistic taste in his aesthetic reflections. III. Some Considerations about the Nude in Contemporary ArtNow it is possible to ask ourselves if these reflections by Cohen can tell us something valid about the role of the nude in the artistic production of our time. On this topic, I have to remind the reader that Peter Schmid, not many years ago, lucidly (even if extremely briefly, in a footnote of an essay)[35] identified in Lucien Freud’s works a recent continuation of Cohen’s attitude towards pictorial representations of the nude; the nude figures painted by Freud, according to Schmid, are not mere reproductions of the outward features of the portrayed people, but represent those people in their dignity. However, it seems necessary to recognize that the prevalent tendency in contemporary art that concerns the representation of the nude seems to be the opposite of this, with a strong eroticisation of the nude figure. We have to highlight, first, that contemporary arts that can have as a central theme the representation of the nude are not the same arts Cohen reflected on. Only marginally does the realisation of lato sensu sculptural or pictorial works have a figurative character; nude figures are not central objects of sculpture or painting.[36] On the contrary, the representation of nude figures is widely used in comics and films; however, in comics and films these figures and their nudity are elements of a story, so they are not represented for themselves as the main objects of a figurative representation. The nudity of the performer is moreover used in different forms of performance art; also here, however, nudity is generally only one of the elements of the performance, not the main object of a representation. On the contrary, nude figures are sometimes the main objects of representation in video art and far more often in photography. In all these arts, both when the nude figure is an element of a story of or a performance and when it is the main object of a representation, it seems clear – or at least I think so – that the predominant tendency is to present the nude figure in contexts that have a strong erotic characterisation. Probably this is clear above all regarding photography: we can think of Robert Mapplethorpe’s male nudes, which are often characterized by the brazen exhibition of the sexual organs of the models; or of David LaChapelle’s surreal, colourful and elaborate images; or of Terry Richardson’s photographs, which are often nearly pornographic, and sometimes actually pornographic; or of the elegant, polished nudes by Helmut Newton. For the most part, the photographs of these authors have a clear erotic connotation, which can be more elegant or more brazen and even pornographic depending on the single case. This does not prevent the photographic representation of nude figures from sometimes appearing to be similar to the sculptural representations of the nude in classical art; among the works of the mentioned photographers, the photographs that may appear to be more similar to those classical models are some female nudes by Helmut Newton, represented in photographs in which we see nothing but the figure of the portrayed model. For example, we can consider the famous Big Nude III: Henrietta, where we see nothing but the represented model – who wears only her shoes – and her shadow on the wall of the studio. Certainly, if we compare this image to a nude figure of classical Greek sculpture (for example the Cnidian Aphrodite or the Aphrodite of Milos), we can perceive some similarity. However, I think that it would be difficult to deny that the figure that is represented in this photograph emanates a great power, a power that shows itself defiantly, almost aggressively, and that is very far from the modest attitude of the Cnidian Aphrodite, or from the noble countenance of the Aphrodite of Milos. This power is clearly a power of seduction, the power to ignite the spectator, or the photographer himself, with erotic desire, more than with a chaste admiration for the beauty of the figure or of its representation, as it happens, or perhaps should happen, in the case of the classical representations of Aphrodite. Now, it could be appropriate to consider that, in the case of photography, we deal with an art form that is far from dwelling in the ivory tower of l’art pour l’art or of musealisation, with its pros and its cons--with the freedom and the irrelevance that this can entail. The photographers I mentioned have produced a relevant part of their works not for art galleries or for a purely artistic enjoyment; they have worked for fashion companies or for pop music companies and also for erotic magazines. These are fields in which there is a strong presence of erotic stirrings, which often belong to the lowest or most vulgar kind of eroticism, as the reduction of the human being (more often, but not exclusively, of the woman) to an object of desire and pleasure. Since performance art and video art have been mentioned, it could be appropriate to mention an artist who can be considered to be an example of a different tendency: Vanessa Beecroft. In the nude scenes filmed by her, every erotic aspect seems to be cancelled, despite the explicit nudity of the models. This elimination of eroticism, however, does not seem to go along with the rejection of the reification of the models, but, on the contrary, it seems to consist in their even more complete reification. Because of the make-up, the hairstyles and above all of the full lack of expressiveness that is required to the models, they seem to be completely reduced to mannequins (or, in some videos or performances, to statues or dead bodies); there is no life in them, they are like artificial beings--they do not appear as women reduced to objects, but as real artificial objects. So, the elimination of eroticism from these representations of nude women appears as a consequence of the complete elimination of their humanity. Considering all these contemporary representations of the nude from the point of view of Cohen’s aesthetics, it is easy to understand that acceptance of Cohen’s aesthetic theories as examined in the previous pages would bring us to reject these works. As we have seen, Cohen rejects eroticism in art because of his radical distinction between erotic desire as an affect (i.e., a feeling that does not produce its object, but is directed to an object--which for erotic desire is a human being--that is already given) and pure feeling as pure love, as love that produces the human being in its dignity. We can indeed think that the eroticism expressed in the photographs by Mapplethorpe, LaChapelle, Richardson and also Newton is an eroticism that has no regard for love of the represented human being in its dignity, and exposes it on the contrary as an object of desire, of the desire we can have for an object. So, this way of representing the nude ultimately is similar to the mass-mediatic reification of the human body (above all of the female body). At the same time, we also see that the elimination of the erotic dimension from artistic representation of the nude does not necessarily correspond to recognition of the dignity of human nature, but, as Beecroft’s works show us, it can also be a consequence of an even more complete reduction of the human body to a mere object. IV. The Necessity of Rethinking Cohen’s Reflections about EroticismThis observation about Beecroft’s works could perhaps bring us to cast some doubts on Cohen’s rejection of eroticism in art: is not the erotic dimension an important aspect of the nature of the human being? Can we really think that the production of the human being as an object of pure love necessarily implies the rejection of the erotic dimension from this human being? If we accept this implication as necessary for art, should not we admit that the human being that is produced by pure feeling as the object of artistic representation is necessarily deprived of one of the important dimensions of its own nature? To answer these questions, we have first to notice that, on a strictly theoretical level, Cohen does not really reject eroticism in art: as we can clearly see in the chapter about lyric poetry, his general thesis is that the bodily dimension of the lovers and of their love must be the object of idealization, of internalization, of transfiguration (Verklärung) by pure love, not of elimination or rejection.[37] On the contrary, when we read Cohen’s specific comments on some poets or works of poetry, we find a clear rejection of eroticism in art; this rejection is a recurring theme in the chapter about lyric poetry, and finds expression in Cohen’s judgements on Goethe’s Venezianische Epigramme, on Heine’s poetry,[38] and on romantic poetry in general. Only in reference to the Song of Songs do we find a slightly less negative judgement on eroticism in poetry; however, in referring to eroticism in this work, Cohen defines the stylistic character of the Song of Songs as dubious, and is concerned with stating clearly that, in this work, eroticism does not break the boundaries of chastity, and that every trace of unchastity is anyway wiped out by the force of another theme--i.e., the moral and political theme of the contrast between the humble condition of the lovers, who are shepherds, and the splendour of the court of king Solomon.[39] Cohen’s comments about works expressing eroticism in figurative arts are much rarer; in fact, they are limited to the already examined considerations about the eccentric eroticism in Dürer’s and Rubens’ representations of nude old women. It is clear that here we have a rejection of this eccentric eroticism, but also that we don’t find, in Cohen’s comments about works of figurative arts, reflections about works expressing any other kind of (sounder or less eccentric) eroticism. Cohen’s praise is on the contrary directed to representations of nude figures in which eroticism is not expressed; we can take once again into consideration his observations about the ephebes in Greek sculpture. Cohen states that the erotic dimension of these figures is transfigured (we find here the same word ‘Verklärung’ that Cohen uses for the bodily dimension of the lovers and of their love in lyric poetry)[40] into chaste admiration for the beauty of the human being; however, in this chaste admiration, the erotic dimension does not seem to have any role; so, it seems to be cancelled, or completely transcended, not really transfigured.[41] Cohen’s comment about Dürer’s Adam and Eve, according to which the figures of this engraving are ‘sublime beyond the ambiguities of sensuality’, is perhaps even clearer in expressing a view according to which, in figures like these, eroticism is transcended and surpassed, not transfigured and idealized. So, Cohen’s rejection of eroticism in art is a feature of his comments on some artworks, but it is not really founded in his theoretical considerations about the idealization of the bodily dimension of the human being. However, an explanation of Cohen’s rejection of eroticism in art has been given in this essay: because of his radical distinction between erotic desire and pure love, Cohen considers eroticism in art to be a hindrance to the purity of feeling. Now we can examine this explanation more deeply and show its insufficiency. Erotic desire, as we have already seen, is an affect, not pure feeling; so, erotic desire cannot be the foundation of art, nor the criterion for judging artworks. However, this does not mean that it has to be fully rejected from art. According to Cohen’s theory, affects cannot be the foundation of art, but this does not mean that they should be excluded from artworks. For example, we can remember that the radical distinction between pure feeling (the foundation of art) and religious love is a central theme of Cohen’s aesthetics:[42] the clarification that only pure feeling, not religious love or faith, is the foundation of every kind of art (including religious art), and that it is aesthetically illegitimate to judge an artwork on the basis of the faith it expresses, is one of Cohen’s main concerns. However, this does not bring Cohen to give a negative judgement of every work of religious art, but rather to comment on many masterpieces of religious art in order to show that what makes them authentic masterpieces is pure feeling. Cohen’s comments on masterpieces of religious art are often intended to show how in those works we can find an idealization of religious subjects: for example, he states that in the story of Christ painted by Giotto we can recognize the ideal story of the human being.[43] Interpretations like this one are intended to show that great art, even in the production of religious works, is free from religious dogmatics; however, this does not mean that the religious affects that are expressed in these works are not authentic. Here we have an idealization of the religious dimension (by means of the liberation of art from strict adherence to religious dogmatics), not its elimination. For eroticism in art, on the contrary, Cohen seems to infer from the radical distinction between erotic desire and pure feeling a consideration of eroticism as a hindrance to the purity of feeling. So, for the erotic dimension of the human being, the necessity of its idealization or transfiguration turns (when Cohen considers specific artworks) into a claim for its elimination and into a negative judgement about artworks in which this elimination is not accomplished. However, the comparison with religious love shows us that the inference from the radical distinction between erotic desire and pure love to the consideration of eroticism in art as a hindrance to the purity of feeling cannot be direct, and needs at least some more reasons. Without these reasons, which are not given by Cohen, the overlap between the idealization of erotic desire and its elimination seems to be merely a confusion. Independently from these incongruities between Cohen’s aesthetic theory and his evaluation of some artworks, we can be certain that Cohen’s theory does not allow for appreciation of any kind of eroticism that reifies the human being, exposing it as a mere object of desire. We can say that, when Cohen criticizes erotic poetry, he rejects an eroticism of this kind, and he rejects a poetry that expresses this attitude: his criticism of poetry that celebrates the art of conquering women is clear.[44] However, this is clearly not the only kind of eroticism--yet it seems to be the only kind taken into consideration by Cohen. Despite his claim that the erotic dimension of the human being has to be idealized, not cancelled, the only kind of eroticism he seems to consider when he examines artworks is the kind he cannot but reject. It is probably impossible to explain what has brought Cohen to embrace such a reductive concept of eroticism in art; perhaps his consideration of sex drive as an affect--which does not produce its object, but is referred to an object that is already given--could have inclined him to consider eroticism in art only as a reification of the human being, as a reduction of the human being to a mere object of desire. However, as we have already seen, this is an inconsistency in comparison to other affects, which cannot produce their object, but are not to be necessarily excluded from art, even if they cannot be the foundation of it. Another factor that could have inclined Cohen to embrace this reductive concept of eroticism is his aversion to the art of romanticism (and perhaps even more to late romanticism and the Decadentism[45] of his time). Anyway, these possible explanations belong all to the slippery field of the biographical and psychological interpretation of Cohen’s intentions, not to the analysis of his texts. Coming back to Cohen’s aesthetic theories as they are documented by his works, now that it seems necessary to recognize that Cohen’s fundamental aesthetic theses do not imply that eroticism has to be banned from art, we can think on the contrary that his very concept of pure feeling as love that produces the human being that is object of artistic representation requires that this human being is produced and loved also in its carnal dimension, as bearer of erotic stirrings and passions. It seems necessary to recognize that the production of the human being as loveworthy by pure feeling, as it includes the love felt by the represented human being and expressed through her or his smile (to mention a feature of the artistic representation of human beings that has great relevance for Cohen), cannot exclude a sound[46] eroticism (and also an eroticism that is not mere animality in the human being, but a truly human eroticism, with the moral aspects that are highlighted by Cohen himself when he considers sex drive as a moral affect), which is far from its impoverished and perverted version that is the reifying eroticism we find in mass media. Perhaps it could be useful to give some examples of this sound eroticism in art; this provides us the opportunity to come back (after some pages where it has been necessary to discuss the topic of eroticism in art mainly with reference to poetry) to the representation of nude figures. Cohen’s theses about the nude as the production of the human being in its original being are profound and convincing, and so are his comments about representations of nude figures in which we can recognize an expression of chaste admiration for the beauty of the human figure in its original being, not of eroticism.[47] These comments can really help us to better understand these artworks and to love them. However, in the history of the artistic representation of nude figures, we can recognize several authentic masterpieces in which the erotic dimension is clearly present and significant, expressing itself in ways that are very far from the eccentric eroticism of Dürer’s or Rubens’ representations of nude old women; examples of a sound eroticism can indeed be nude figures such as Tiziano’s Venus of Urbino[48] or Manet’s Olympia (which is a sort of modern revisited version of Tiziano’s Venus), or Goya’s Maja Desnuda. It seems impossible to deny that these paintings are authentic masterpieces; moreover, it seems also impossible to deny that eroticism is an important dimension in them and that at the same time the main figure we see in these paintings is worthy of authentic love and is produced by love itself. So, masterpieces like these show us the need to recognize a role for a sound eroticism in art, and make Cohen’s concept of eroticism in art appear quite reductive. In several other contexts, I have expressed my conviction that we have to recognize in Cohen’s aesthetics a particular kind of topicality in relation to contemporary art; this topicality, I think, does not consist in a correspondence between Cohen’s aesthetics and the main tendencies of contemporary art, but – just on the contrary – in the fact that Cohen’s concept of pure feeling as love for the human being can be the fundament of a necessary criticism of an anti-humanistic art, of an art that often expresses no love for the human being, and which also tramples on human dignity with sarcasm.[49] This conviction that in Cohen’s aesthetics we can find the fundament of a profound criticism of the main tendencies of contemporary art can concern also the specific question of eroticism in the artistic representation of nude figures; however, on this specific topic, we have to admit that (though we can find in Cohen’s thought a fundament to criticize the reifying eroticism that is so strongly present in contemporary photography or in other arts) his rejection of reifying eroticism is not accompanied by the development of any better concept of eroticism in art than the reifying one. Hence, Cohen’s stance on eroticism in art is a complete rejection, but the missed recognition of a sound eroticism and of a role for it in art seems to have the consequence that the human being produced by pure feeling as the main object of artistic representation appears impoverished of one of its important dimensions. Therefore, the necessity to recover this dimension of the human being in art requires that we do not settle for Cohen’s criticism, but that we look beyond it. ReferencesCohen, Hermann, Kants Begründung der Ästhetik. Berlin: Dümmler, 1889 (in 2009 the book was anastatically reprinted by Olms with an introduction by Helmut Holzhey as volume 3 of Cohen’s Werke). ------------, System der Philosophie. Dritter Teil: Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls. 2 vols., Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1912 (in 1982 the two volumes were anastatically reprinted by Olms with an introduction by Gerd Wolandt as volumes 8 and 9 of Cohen’s Werke). ------------, Der Begriff der Religion im System der Philosophie. Gießen: Töpelmann, 1915 (in 1996 the book was anastatically reprinted by Olms with an introduction by Andrea Poma as volume 10 of Cohen’s Werke). Gamba, Ezio, La legalità del sentimento puro. L’estetica di Hermann Cohen come modello di una filosofia della cultura. Milano-Udine: Mimesis, 2008. ------------, ‘The Problem of Individuality in Hermann Cohen’s Aesthetics.’ RUDN Journal of Philosophy 23, no. 4 (2019): 413-419. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22363/2313-2302-2019-23-4-413-419. Poma, Andrea, Yearning for Form and other Essays on Hermann Cohen’s Thought. Dordrecht: Springer, 2006. Peter A. Schmid, ‘Die Vervollkommnung der Sittlichkeit in der Nacktheit: Zur Erzeugung des Menschen in der Kunst.’ Zeitschrift für Religions- und Geistesgeschichte 62, no. 2 (2010): 175-182. Wiedebach, Hartwig, Die Bedeutung der Nationalität für Hermann Cohen. Hildesheim-Zürich-New York: Olms, 1997. Revised English translation by William Templer, The National Element in Hermann Cohen’s Philosophy and Religion. Leiden: Brill, 2012. [1] I have to thank Helmut Holzhey, who twenty years ago, during our first encounter, invited me to reflect about the opposition of aesthetics and erotics in Hermann Cohen’s aesthetics; his suggestion arrives only now to this tardive realization. [2] Hermann Cohen, System der Philosophie. Dritter Teil: Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls (2 vols., Bruno Cassirer: Berlin, 1912; in 1982 the two volumes were anastatically reprinted by Olms with an introduction by Gerd Wolandt as volumes 8 and 9 of Cohen’s Werke). [3] Winckelmann’s historical role for the birth of aesthetics is object of wide consideration by Cohen in the Historische Einleitung of Kants Begründung der Ästhetik (Berlin: Dümmler, 1889; in 2009 the book was anastatically reprinted by Olms with an introduction by Helmut Holzhey as volume 3 of Cohen’s Werke), 37-62. In Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls Cohen does not present a wide historical exposition of the birth of aesthetics as he does in Kants Begründung der Ästhetik; however, the historical considerations scattered through Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls about the birth of aesthetics or about the history of philosophical reflections on beauty and art before Kant are usually short recaps of reflections that are more widely presented in Kants Begründung der Ästhetik; the continuity between the two books for what concerns this topic is clear. [4] Regarding Cohen’s concept of figure, see Andrea Poma, Yearning for Form and other Essays on Hermann Cohen’s Thought (Dordrecht: Springer, 2006), 147-152 and Ezio Gamba, La legalità del sentimento puro. L’estetica di Hermann Cohen come modello di una filosofia della cultura (Milano-Udine: Mimesis, 2008), 135-138. [5] The reason for the popularity of this theme among painters (a popularity that is clearly greater than the religious or historical relevance of the biblical episode) most likely lies indeed in the possibility of painting the figure of the nude beautiful woman and of the two prestigious old men with splendid clothes. [6] Obviously, when the secondary elements of the representation of the episode are reduced, also the explicit or clearly recognizable references to a specific story are restricted; for example, in Rembrandt’s Susanna in the Bath in The Hague, we see only the figure of Susanna, because the Elders are still hidden, and only by looking attentively we can glimpse the face of one of them in the vegetation. Therefore, this female figure can appear as a nude figure that is represented for itself, not as an element of a story; so, contrary to many other representations of Susanna, this figure could seem to be a good example for Cohen’s reflections about the nude; in the next pages we shall have to take Rembrandt’s representations of Susanna into consideration again. [7] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 177; here Cohen mentions amazons as female analogous to ephebes, even if notoriously in the most famous representations of amazons in Greek sculpture their figures are only partially nude. [8] Regarding the individuality of the human beings that are object of artistic representation, see Ezio Gamba, ‘The Problem of Individuality in Hermann Cohen’s Aesthetics,’ RUDN Journal of Philosophy 23, no. 4 (2019): 413-419, https://doi.org/10.22363/2313-2302-2019-23-4-413-419, or Gamba, La legalità del sentimento puro, 203-207. [9] The Artemision Bronze that we can see in the National Museum of Athens can be a meaningful example of this: it could represent Zeus or Poseidon, and the figure is represented in the act of throwing something… but what is he throwing? The ancient object has been lost. Perhaps it could be a trident, so the represented god would be Poseidon; perhaps it could be a thunderbolt, so the represented god would be Zeus. The loss of this sole element that is added to the nude figure of the god prevents us from identifying the god himself. [10] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 176 and II, 280. [11] Cohen devotes to the topic of the nude p. 176-180 of vol. I of Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls; the reference to Eros and Aphrodite is at the beginning of these reflections. The Satyr is not mentioned here; however, its relation to Eros and Aphrodite is the object of Cohen’s reflections some pages earlier, on p. 173-174. [12] One may wonder – but at this time I have no resources to answer this question – if the fact that Cohen mentions together Eros, Aphrodite and the Satyr in so narrow a relationship (reminding the reader that Eros is often an attributive figure of Aphrodite and considering the Satyr to be a figure of contrast with relation to Eros) means that he implicitly refers to the sculptural group of the Aphrodite of Delos, which was found in the archaeological excavations of Delos in 1904, eight years before the publication of Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls. [13] Praxiteles sculpted two representations of the Satyr, known as Wine Pouring Satyr and Resting Satyr; both have survived in many copies. The reader of Cohen’s Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls could wonder which of those representations is the one Cohen refers to; only on p. 286 of the first volume of his work (after Praxiteles’ Satyr has sometimes been mentioned without specification) does Cohen make reference to the ‘kapitolinische Satyr’, i.e. the statue we can see in the Capitoline Museum of Rome, and which is a copy of the Resting Satyr. However, the precise identification of the statue is not an important problem: the features of Praxiteles’ Satyr that are highlighted by Cohen can be found both in the Wine Pouring Satyr and in the Resting Satyr. We can think, accordingly, that Cohen’s reflections about Praxiteles’ Satyr do not concern a single statue, but Praxiteles’ way of representing the Satyr, whereas the specific reference to the statue in Rome could be just an example, which Cohen brings in order to highlight a feature of this figure--his smile--that perhaps Cohen considers particularly evident in this specific statue. [14] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 286. [15] Praxiteles’ works are certainly the main example of the representation of the Satyr in Cohen’s aesthetics; however, Cohen also mentions the Satyr represented by Böcklin in his painting Nymph and Satyr (see Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 287-288). Moreover, Cohen reminds that in some ancient sculptural works the Satyr holds the child Dionysus in his arms (see Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 285); this is not a feature of Praxiteles’ representations of the Satyr, so it is clear that, even in ancient sculpture, Praxiteles’ statues are not the only works Cohen’s reflections are referred to. [16] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 173. [17] Introducing the role of the sex drive in art, Cohen writes that the sex drive is a moral affect, which is at the base of ‘the fundamental form of family and of ancestry (die Grundform der Familie und des Stammes)’ (Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 168). We can understand, therefore, that for Cohen the sex drive in the human being is not a merely an animal urge; however, in the figure of the Satyr-- the representation of animality in the human being--the sex drive appears prima facie only or mainly in its animal aspect, as an animal urge. However, pure love redeems this animal drive to human love. [18] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 174, 285-286 and 288. [19] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 174. [20] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 179-180. [21] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 168. [22] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 26. [23] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 44-47. As it is pointed out by Hartwig Wiedebach, even if Cohen considers Goethe’s poetry as the paradigm of lyric poetry (Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 30), a fundamental historical role for the idealization of sexual love in poetry and for its emancipation from the blame that can be casted on it by a dogmatic religious morality has to be recognized in Dante’s Divina commedia. See Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 321-324 and Hartwig Wiedebach, Die Bedeutung der Nationalität für Hermann Cohen (Hildesheim-Zürich-New York: Olms, 1997), 210; revised English translation by William Templer, The National Element in Hermann Cohen’s Philosophy and Religion (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 158-159. [24] For the meaning of ‘soul’ in Cohen’s theory of the figure, see Gamba, La legalità del sentimento puro, 135; for the expressions ‘Natur des Menschen’ and ‘Mensch der Natur’, see Poma, Yearning for Form, 147-152 and Gamba, La legalità del sentimento puro, 136. [25] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 372. Perhaps it could be considered appropriate to ask if these nude figures are sublime beyond sensuality or only beyond the ambiguities of sensuality, so that they could express a sensuality freed of its ambiguities. However, Cohen does not take into consideration the possibility of any kind of freed sensuality; on the contrary, in its aesthetics, sensuality is always linked to ugliness and to animality (some examples will be taken into consideration in the next pages); so, it is clear that in the context of Cohen’s aesthetics these figures can be judged as sublime beyond the ambiguities of sensuality only because they are sublime beyond sensuality. [26] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 372. [27] Actually, there are two paintings by Rembrandt known as Susanna and the Elders or Susanna in the Bath: in one of them (in The Hague) the Elders are still hidden, so the only figure we see is Susanna; only by looking attentively can we glimpse the face of one of the Elders among the leaves. In the second (in Berlin), on the contrary, we see the Elders threatening Susanna (this is clearly a more usual way to represent this biblical episode). In the context of the second volume, Cohen uses the plural ‘Susannen’, so he refers to both; in the first volume, on the contrary, he writes ‘Susanna’, but there is no sign that can allow us to understand to which of the two paintings Cohen refers. However, the main female figure has similar features in both paintings, so it is not so important to refer Cohen’s judgement specifically to one of these paintings; we can also think that the name ‘Susanna’ refers to the figure of this biblical woman in both of Rembrandt’s representations of her, not specifically to one of these two works. [28] In his reflections about Raffaello’s portrait of pope Leo X, which are so important for Cohen’s theory of Humor, Cohen considers the ugliness of the represented man as the expression of his sensuality; in this case, however, Raffaello’s art makes this ugly man loveworthy. See Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 354-356. The difference between Raffaello’s portrait of Leo X and Dürer’s engravings representing old nude women is that, in these engravings, sensuality is not accompanied by the ‘moral passion of the character (sittliche Leidenschaft des Charakters)’, which in the portrait of Leo X is expressed above all by the mouth and the hands of the figure. For this reason, the sensuality in Dürer’s previously mentioned engravings does not rouse sympathy, and exposes itself to derision. For this contrast, it is possible to compare Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 373 with I, 303-304. [29] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 373. On II, 372, Cohen points out the mocking expression of the figure represented in Dürer’s Great Fortune; it is appropriate to notice that, when he explains the importance of the smile in figures like the Satyr, he clearly distinguishes this smile from an expression of derision (Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 286-287 and II, 280), and mentions, as example of a mocking smile that expresses Schadenfreude (malicious glee for the bad fate of other people), the sculptural representation of Medusa on a relief in Selinunte (Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 280). By pointing out the mocking expression of the figure in Dürer’s Great Fortune, Cohen clearly distinguish her expression from the smile that is the sign of Humor, and at the same time recognizes that this figure belongs to a genre--representations of monstrous beings that are intended to rouse horror and fear. [30] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 389. Here, moreover, Cohen highlights that Rembrandt paints the figure of Venus in his Venus and Cupid as a portrait of his partner Hendrickje Stoffels, and that this female figure is dressed, not nude as we can expect from a representation of Venus (as in Praxiteles’ Cnidian Aphrodite, for example). The figure of Hendrickje Stoffels in Rembrandt’s works, and particularly in her portrait in the Louvre, is for Cohen the main example of Rembrandt’s representation of figures that are far from classical beauty as loveworthy (Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 294 and II, 389-390); therefore, by means of pointing out the fact that Rembrandt does not portray her in the nude even when she is represented as Venus, Cohen highlights the distance that separates, in Rembrandt’s works, his Humor from his representations of nude figures. The incongruity with Cohen’s statement about the figure of Rembrandt’s Susanna in the context of the first volume is clear. [31] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 389. This brief observation by Cohen is clearly not consistent with the whole of his aesthetic theory; here Cohen’s aesthetics falls into the enunciation of precepts (or into the expression of Cohen’s personal taste as an artistic norm). [32] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 389. [33] For a meaningful occurrence of this word, see Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 389. [34] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 294; moreover, on the previous page, after stating that even in Rembrandt’s infrequent representations of nude figures his interest is always mainly directed to the problem of ugliness, Cohen also recognizes that, in these representations, this problem does not always appear with full energy. [35] Peter A. Schmid, ‘Die Vervollkommnung der Sittlichkeit in der Nacktheit: Zur Erzeugung des Menschen in der Kunst,’ Zeitschrift für Religions- und Geistesgeschichte 62, no. 2 (2010): 181. [36] An important exception can be represented by some works belonging to neopop art, particularly some works by Jeff Koons, as his statues representing Lady Gaga, about which I think what I write in the following about eroticism in photography will apply. [37] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 46. It could be surprising that on p. 393 of the first volume of Cohen’s Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls we read that in lyric poetry the ‘unity of body and soul […] is totally transposed to the side of the soul’ (I quote this sentence as it is translated by William Templer in Wiedebach, The National Element, 163). The aim of this statement, in its context, is to point out clearly the difference between epic poetry--with its stories of heroes and battles--and lyric poetry, which is focussed on the inner world of the individual, without consideration for history and society. Hence, in the above statement, we have to understand the word ‘body’ as the outward dimension of the human being, as the connection of the human being to history and society. So, this statement by Cohen must not be understood as an assertion of the irrelevance of the body in lyric poetry; moreover, this understanding of this sentence would be inconsistent with Cohen’s reflections on the important role of tears as bodily testimony of woe in lyric poetry (Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 205 and II, 30 and 46-47) or on Goethe’s expression ‘my innards burn (es brennt mein Eingeweide)’ (Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 30 and 188). However, this statement by Cohen can be seen as an example of how Cohen, in developing his own thesis of the idealization of the body in poetry, is sometimes inclined to convert it into a claim that the body has to be excluded from poetry, or at least to use expressions that can be understood as assertions of the irrelevance of the body itself. [38] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 48-49. [39] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 37-39. [40] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, I, 179. [41] It is possible to add an observation about the relation between poetry and figurative arts: Cohen writes that the relief representing Perseus and Andromeda in the Capitoline Museum of Rome can be considered to be a figurative correspondent to lyric poetry, because the love that is expressed by the two figures is the love that lyric poetry is centred on. Cohen also states that, if we imagine these two figures could speak, we should imagine that their speech consists of a love poem or a love song of classical purity, equal to the classical purity of the relief itself. Moreover, examining this relief, Cohen highlights the chastity expressed by the figures (we can notice that the nudity of Perseus is not a hindrance to this expression of chastity) and by their gestures (Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 53). Here, Cohen’s comment about the chastity of the scene and of the figures appears convincing, but the choice of this relief as an example of a figurative correspondent to lyric poetry can cause some doubts: it does not simply represent a love scene, but a scene of triumph. In the relief, the valour of the hero, who has defeated the monster we see in the low part of the relief, is at least as much important as the love between him and the woman he has saved. We can think, perhaps, that the chastity of the scene is a consequence of the fact that the virile courage of Perseus has to find its correspondent in the feminine virtue of the modesty of Andromeda, and that this courage must include respect for the woman and control of his own instincts. So, their love could merely be the consequence of their virtues, not the main theme of the relief; this interpretation could mean that the chastity of the scene is not a consequence of the authenticity of the love between the two characters (which would be the same love of lyric poetry), but of the fact that the represented scene is not exclusively a love scene. Anyway, independently from any attempted interpretation like this one, the fact that this relief represents a scene of triumph, not simply a love scene, and expresses a celebration of heroic courage, not only the love between the two figures, makes Cohen’s choice of this relief as example of a figurative correspondent to lyric poetry (and Cohen’s claim that in the chastity of this relief we can recognize a figurative representation of the chastity of the love sung by lyric poetry) very dubious. [42] This radical distinction is a central and recurring theme not only in Cohen’s Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, but also in the chapter about aesthetics and religion in his book Der Begriff der Religion im System der Philosophie (Gießen: Töpelmann, 1915; in 1996 the book was anastatically reprinted by Olms with an introduction by Andrea Poma as volume 10 of Cohen’s Werke). [43] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 331. [44] Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 47. [45] See the reference to decadent poetry in relation with the topic of eroticism in Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 26. [46] Cohen considers as a clear sign of the aesthetic inauthenticity of a work of poetry the fact that in it, love appears as illness or madness (this is certainly a romantic topos, but Cohen shows that its origins are ancient, as we can see in Euripides’s tragedies). On the contrary, purity of love is health; moreover, Cohen associates this consideration of love as illness to unchastity (see Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 24-25 and 51-53). Recognizing a positive role of eroticism in art, accordingly, implies recognizing that eroticism can be sound, and that only sound eroticism, not a sick or perverted one, can have this positive role. [47] Obviously, recognizing the importance of the erotic dimension in the human being does not mean that this dimension has to be expressed in every figure (the same clearly applies to many other important dimensions and affects, for example religious love); it means, however, that this dimension cannot be banned from art. [48] Tiziano is sometimes briefly mentioned in Cohen’s Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls; as we have seen, one of these mentions directly concerns the representation of the nude. However, neither the Venus of Urbino nor any other work by Tiziano representing nude figures are expressly mentioned, and above all no reflection is devoted to the eroticism we can find in a work like his famous Venus. In the context in which Cohen associates Tiziano with Rembrandt because they both use nudity to represent beauty--not ugliness--contrary to Rubens (Cohen, Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls, II, 389), he states, a few lines before mentioning Tiziano, that Rembrandt never plays with the fire of sensuality like Rubens; this judgement is referred by Cohen to Rembrandt, not explicitly to Tiziano. Should the context bring us to think that this statement expresses Cohen’s views on Tiziano’s art too? If we go on reading, we see that Cohen, just after associating Tiziano with Rembrandt because they both use nudity to represent beauty, writes that Rembrandt’s interest goes beyond the representation of Venus, and praises Rembrandt for his representation of Venus as a dressed figure (see footnote 30 of this essay): if he had represented her in the nude, as we could expect from a representation of Venus, this representation of an ugly (or far from classical beauty) figure in the nude could have been not undoubtedly different from Rubens’s figures or from many representations of nude old women--the ugliness of which is made presentable by means of stirrings of sensuality. It seems clear that here there is an implicit reference to Tiziano’s famous Venus of Urbino, and that Cohen highlights how Rembrandt’s interest goes far beyond the representation of beautiful nude figures like Tiziano’s representation of Venus; so, just after associating Tiziano with Rembrandt, Cohen shows Rembrandt’s greater relevance for aesthetics by pointing out his Humor as representation of ugly figures as loveworthy. However, this appraisal of Rembrant’s significance for aesthetics does not imply a negative judgement about Tiziano’s Venus of Urbino or about any other of his works. Should we perhaps think that Cohen’s praise of Rembrandt’s representation of Venus, which avoids the risks of sensuality with its ambiguities, implies criticism for Tiziano’s Venus, which in her nudity does not seem to avoid them? Actually, the risk avoided by Rembrandt is the risk connected with the representation of ugly nude figures, but Tiziano’s Venus of Urbino (as Cohen states for Tiziano’s nude figures overall) represents a beautiful nude figure; therefore, this figure is also not subject to that risk. At the end of these considerations about Cohen’s implicit reference to Tiziano’s Venus of Urbino, we cannot but recognize that we do not really know whether he considered this figure ‘sublime beyond the ambiguities of sensuality’, like Dürer’s figures of Adam and Eve (so, Cohen’s judgement according to which Rembrandt never plays with the fire of sensuality would express Cohen’s view on Tiziano’s art too), or he acknowledged the eroticism of this representation. However, in the absence of specific comments by Cohen on this painting, we have to recognize that the first possibility seems to be more consistent with the whole of Cohen’s comments about young and beautiful nude figures in painting and sculpture; we can anyway think that giving attention to this painting by Tiziano could have provided Cohen the opportunity to reflect on the possibility of a sound eroticism in figurative arts, but Cohen has not seized this opportunity. [49] See for example E. Gamba, La legalità del sentimento puro, p. 319-328. |

|

Artikelnachweis: https://www.theomag.de/135/eg01.htm |

Obviously these ephebes or figures of the same kind are the most evident examples of the production of human figures by pure feeling without any reference to historical or social features; we can, however, recognize as similar to them other figures, the representation of which includes some particular features that are reduced to a minimum. For example, many representations of Greek gods, who have a precise identity, are represented without reference to any of the specific episodes that mythology tells about them; sometimes we can identify them by a single element that appears in the sculpture besides their nude figures,

Obviously these ephebes or figures of the same kind are the most evident examples of the production of human figures by pure feeling without any reference to historical or social features; we can, however, recognize as similar to them other figures, the representation of which includes some particular features that are reduced to a minimum. For example, many representations of Greek gods, who have a precise identity, are represented without reference to any of the specific episodes that mythology tells about them; sometimes we can identify them by a single element that appears in the sculpture besides their nude figures, In Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls Praxiteles is often mentioned with reference to a third nude figure, which is very important for Cohen’s aesthetics, and which is put by him in relation to Aphrodite and Eros, even if he does not mention this figure in the pages he specifically devotes to the topic of the nude; this figure is the Satyr.

In Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls Praxiteles is often mentioned with reference to a third nude figure, which is very important for Cohen’s aesthetics, and which is put by him in relation to Aphrodite and Eros, even if he does not mention this figure in the pages he specifically devotes to the topic of the nude; this figure is the Satyr. This does not imply that Cohen does not reflect on nude figures in painting; these reflections, however, are not further theoretical developments of his theses on the artistic representation of nude figures as the representation of the human being in its original being; rather, they are comments about some specific artworks or painters. These comments, however, can be important in order to comprehend Cohen’s view on eroticism in art; we find them mainly in the chapter about painting in the second volume of Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls.

This does not imply that Cohen does not reflect on nude figures in painting; these reflections, however, are not further theoretical developments of his theses on the artistic representation of nude figures as the representation of the human being in its original being; rather, they are comments about some specific artworks or painters. These comments, however, can be important in order to comprehend Cohen’s view on eroticism in art; we find them mainly in the chapter about painting in the second volume of Ästhetik des reinen Gefühls.